Read any fashion or textiles company trading statement and it will invariably begin with “Revenue growth was…”, and then describe whether growth was “in-line” or “missed” expectations for the reporting period.

For investors, revenue growth is often the starting point for understanding how a company is performing, whether it will generate more profit (or loss), and whether this will impact its share price and valuation. The key components of revenue growth for any company are volume and price (together often referred to as organic growth), currency (FX) impacts and then growth (or contraction) associated with acquisitions or divestments.

However, as brands continue to focus on sustainability, should volume growth still be used by investors in the textile sector as a valuation driver? Where will revenue growth come from in the future if not from volume growth?

Overtaxing resources

Recently, fashion brands have focused their marketing to consumers on their sustainability credentials, but when they market themselves to investors, they continue to focus on revenue growth driven by increasing volume. This focus on increasing production to increase profit continues to overtax the natural resources on which the growth of most companies depends while accelerating climate change.

As a result, many NGOs, environmental authorities and consumers have concluded that unchecked consumption is incompatible with our resource-constrained world. Nowhere is this so clear in the textile, apparel and clothing (TAC) sector as in fast fashion – inexpensive clothing produced rapidly by mass-market retailers in response to the latest trends.

Greater focus on unchecked growth presents both a financial risk and opportunity for investors.

Concerns have been raised that sustainability claims in the fashion industry often constitute nothing more than greenwashing to improve brand image and boost sales. Companies maintain a majority of their practices as business-as-usual, producing just a small fraction of their products sustainably in order to give their whole brand a green guise. This, in turn, misleads consumers with regard to the overall impact of their brand on the environment.

Indeed, these concerns are increasingly attracting the attention of regulators who have begun to crack down on corporate greenwashing. In a recent survey of global websites, the International Consumer Protection and Enforcement Network (ICPEN), a network of consumer protection authorities from over 65 countries, found as many as 40% of environmental claims across a range of consumer businesses could be misleading the public.

The Netherlands Authority for Consumers and Markets (ACM) has already begun imposing fines of up to €900,000 per violation or a percentage of the turnover of those found to be making misleading environmental claims. Furthermore, the UK’s Competition and Market Authority (CMA) recently published a “Green Claims Code” to help businesses comply with the law. The CMA also cautioned that it “stands ready to take action against offending firms” and plans to carry out a full review of deceptive claims next year.

Greenwashing

If a company is found guilty of greenwashing, this will likely have a negative impact on its market value. Indeed, some research has shown that corporate greenwashing can adversely affect financial performance. This is due to the detrimental effect greenwashing exhibits on a company’s reputation with stakeholders such as consumers, employees and organizations with which it conducts business. Additionally, greenwashing firms may incur significant fines, penalties and clean-up costs.

Action to address this risk is especially critical as the environmental consequences of the fashion industry are increasingly brought to light and more companies are held to account. Additionally, regulatory changes in favour of extended producer responsibility or internalisation of environmental externalities could further intensify the pressure on fashion companies.

We therefore challenge investors and companies to consider what value in textiles and fashion sectors could look like when growth (in volume) is a dirty word. Such valuations should take into account the downside risks to a company and its shareholders from failing to reduce its environmental footprint (e.g. greenhouse gas emissions, wastewater discharge), as well as the upside potential from minimising its environmental impact (e.g. developing more sustainable revenue streams: circular fashion, clothing rental), and the benefits of capitalising on rising market demand for sustainable clothing.

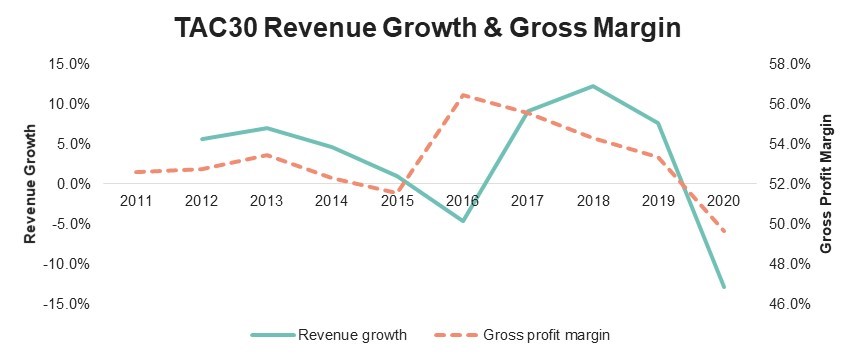

Already, companies today do not necessarily see a link between revenue growth and gross profit margin expansion. In effect, the investors will reduce or remove the transition risk discount implicit in the valuation of such companies.

Model shifts

What would a business model shift look like if growth is a dirty word?

Just as Netflix initially only rented DVDs and later shifted to online streaming, business models can and do change. If the H&M of the future is no longer known for its “new” clothes, how will revenue and growth be generated? The transition in revenue will come from innovation and diversification in offering, with an increasing shift to services as well as products.

Resale

We anticipate that technology will continue to play a key role in these revenue stream shifts, with a continuing focus on the resale market and the introduction of Resale-as-a-Service to some TAC company websites, as in the case of Madewell, lululemon and Levi’s.

This provides a revenue stream to the brand from the booming second-hand market. Indeed, those ready to lead the resale race may enjoy sizable gains, as this market is projected to be worth US$77 billion in the next five years and is growing eleven times faster than traditional retail. Since 2015, we estimate almost $3.5 billion of public and private capital has been raised by these fashion-focused resellers, of which $2.5 billion was raised since 2019.

Some online resellers are even moving into retail locations. For example, Madewell and thredUP recently tested a secondhand store in New York. The pop-up shop included a mending station and QR codes that visitors could scan to educate themselves on fashion waste. Indeed, retail stores may very well focus as much on services and experience as on products in the future.

Revitalising

Another promising revenue stream for brands could involve incentivising consumers to revitalise old clothing for their own use by having it repaired, repurposed or recycled – through the brand of course – to generate new value using fewer resources. Some companies are already utilising the post-consumer model by providing central locations with a focus on clothing repair, resale, reuse and recycling. Patagonia’s Worn Wear recycling and repair programme, for example, extends the product lifecycle by allowing customers the option to trade in their used gear for credit. Similarly, Zalando’s Zircle app offers consumers the opportunity to sell fashion items back for credit. Zalando then resells the used items through its new resale category. Last October, Zalando launched the app in 13 markets and received 100,000 items in the first month. The aim is to prolong the life of 50 million items of clothing by 2023.

Rental

Yet another rapidly growing market in the sustainable fashion industry is rental. Rent the Runway, a leader in this space, is a subscription fashion service that enables customers to rent designer styles for work, weekends and events. In essence, brands could capitalise on both trends by introducing a clothing subscription model – clothes-as-a-service – where a monthly fee allows the customer to effectively “rent” clothing which is then returned at the end of a selected period.

Seasons

The continuous rounds of seasonal collections released by brands constitute a significant contributor to fashion’s pernicious growth problem. For a fast fashion brand this can be as many as 12–48 mini-collections a year, but even large luxury brands like Chanel can have around six collections a year. Some companies are attempting to address this by designing fewer items, with an emphasis on timelessness and durability. Swedish brand Asket, for example, only offers a single, permanent collection of high-quality clothing. There are no on-trend designs or seasonal pieces. Similarly, VETTA curates a limited number of five-piece capsule collections each of which can be mixed and matched to create 30 outfits, giving consumers more for less.

This personalisation and service-orientated focus coupled with innovative technologies could provide a new source of revenue for the fashion industry, helping to break the vicious overproduction/overconsumption cycle while reducing its environmental impact.

Digital fashion

Finally, the rise of digital fashion also presents a potential revenue stream for brands. The “metaverse” is a blurring the lines between the virtual and the real, and consumers are intrigued. Fortnite, for example, generated $5.1 billion in revenue for Epic Games in 2020. The source of this revenue was not players paying to play the game, as it is free to play. Rather, it was generated by players purchasing “cosmetics” (i.e. character costumes) or dance moves simply to look good while playing. In Fortnite you can attend concerts (with 50 million of your closest friends) and dress how you please. Earlier this year, Balenciaga and Epic Games announced a collaboration to bring the brand’s clothing and its signatures into the game.

This marked Fortnite’s first collaboration with a luxury fashion brand, although it has already done collaborations with Nike (who are gearing up on making and selling virtual branded sneakers and apparel in the metaverse. The ability for brands to tap into this revenue stream presents a significant and growing opportunity. With traditional brands, the digital is often matched with a physical version of the product. However, digital-only brands like Auroboros, are pushing the boundaries of what fashion is. Other digital-based revenue streams such as Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs), digital collectables, are also rising in popularity and truly decouple volume from value. Luxury brands, in particular, have embraced this new blockchain-driven technology.

Conclusion

The present link between higher volume growth and a higher valuation is unsustainable on many levels, but this should not be muddled with a degrowth strategy. It is clear that growing profits while adopting sustainable business practices is perfectly possible – investors should be encouraging and thinking about how brands can embrace this trend. However, ultimately we will still need to clothe 10 billion people by 2050 – doing this sustainably remains key.